“...the historical other is being excluded even as such exclusion is denounced and lamented, with much fanfare…”

Kate Manne, 2018 (p. 236)

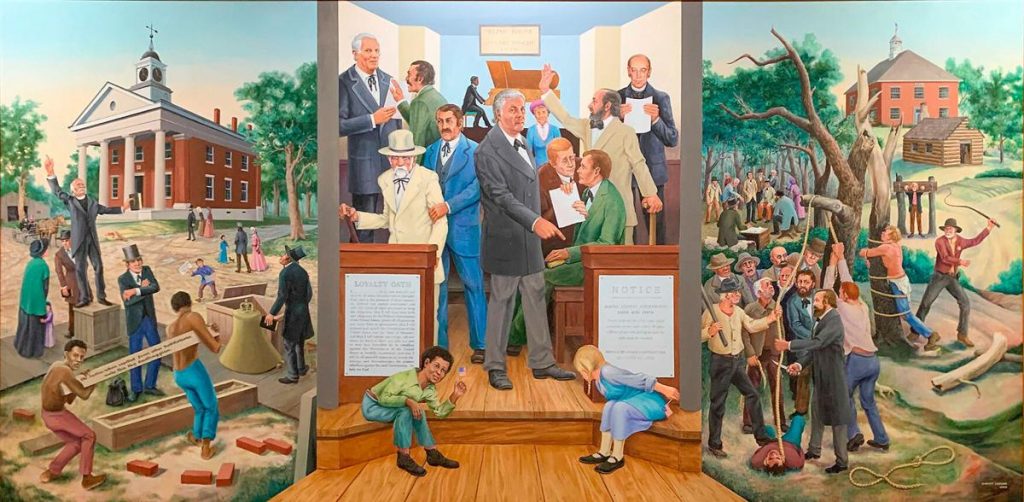

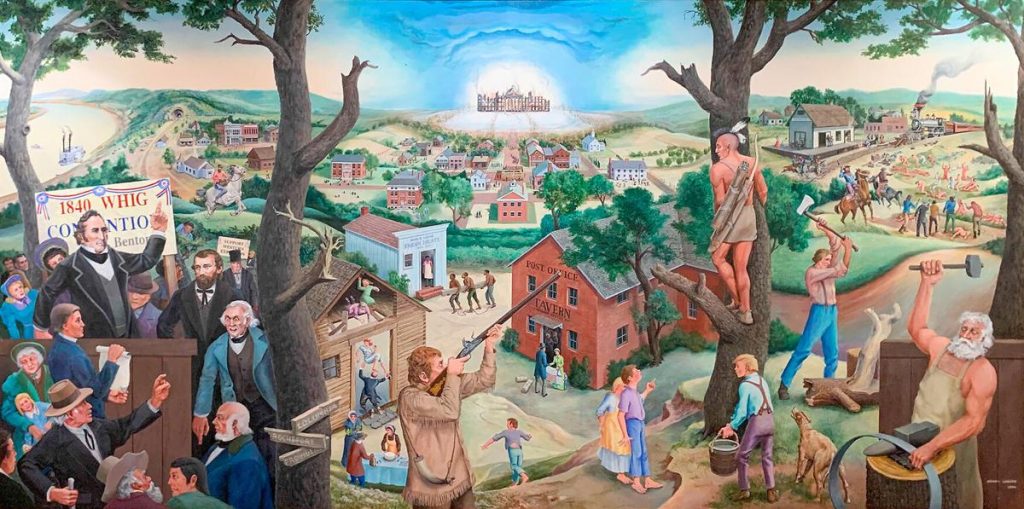

The Courthouse of Boone County, Missouri has prominent murals adorning its walls that give an unflattering depiction of BIPOC and women. While conversations may be held as to the historical or artistic relevancy of such work, the primary concern is that these images set and reinforce an insidious tone within the halls of our Courthouse. We feel these representations to be grossly inappropriate to the settings, and hold that these images be removed from their present location to a more appropriate gallery, if preserved.

"I see no politics in the murals; I see no advocacy; I certainly see no celebration or endorsement of abhorrent things about our history," Powell explained. "I certainly don’t want our justice system or those who shape it and administer it to forget or fail to know the lessons of history, and I see great value to a somewhat in-your-face confrontation with those lessons whenever we are in the community’s hall of justice trying to produce justice." (bold emphasis added)

Bill Powell, 9/28/2021 in KOMU article: Boone County Commission hears public comment regarding courthouse murals, by Julia DeFrank.

The title and the quote herewith are a response to Mr. Powell and Judge Kevin Crane, and are borrowed from the work of Kate Manne (2018) in Melancholy Whiteness (or, Shame-Faced in Shadows).

“...a very general problem: how to break the news to the historically privileged of their shameful, ongoing legacy of, e.g., colonialism, white supremacy, and racism, without inducing the kind of shame that seeks an irrevocable break between the self and the other—or, simply, to break one or the other, if not both, of these subjects” (p. 233)

Kate Manne, 2018 (p. 233)

Mr. Powell also claimed that the mural image of the man on the ground -- with the rope around his neck was not black. He conceded (due to the context provided in the mural description) that the image depicted James S. Rollins's intervention into an attempted lynching -- a scene of extra-judicial vigilante mob violence. The enslaved man on the ground was named Hiram -- has a name and yes, he was Black. Thank you Zachary Dowdle for retrieving him from the archives of obscurity in “’Hang Him Decently and in Order’: Order, Politics, and the 1853 Lynching of Hiram, a Slave”. See more of the works of Zachary Dowdle, PhD.

The bolded text below was included in the remarks I made last night -- I believe they are potent claims derived from Chimamanda Adiche’s powerful TedTalk -- The Danger of the Single Story.

First, she notes one way to “...create a single story, [is to] show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.” Next, Adiche commented on power and who controls the narrative of people who are othered, a reckoning Mr. Powell seems to be struggling to acknowledge:

“It is impossible to talk about a single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is "nkali." It's a noun that loosely translates to "to be greater than another." Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali: How they are told, who tells them, when they're told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power.”

She explains further:

Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, "secondly." Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.

I invite Columbians to ponder the ways that Black, Brown, Indigenous (BIPOC), LBGTQIA**, gender non-conforming, and those with disabilities, cognitive and physical, are portrayed through our community through print and social media and community organizations. Often they are represented through binary logic which are stereotypes or what I would call limited or fixed representations where there is no room for multiple ways of being in the world.

I reject the singularity of subjugation in the imagery which presents oppressed people as the background -- minimized pictorially even as hard to see and make out. White men, their power, and violence are over-projected via size in every scene. This is a narrative that must be dismantled and white people need to lead in making it happen.

Next, peruse our local media outlets’ coverage of the murals and take note of who is and who is not quoted. For example, analyze the reporting of Columbia Missourian vs. KOMU, ABC17, and the Columbia Tribune; because the Missourian is the training ground for journalists. You will find that typically all men with privilege and power are quoted FIRST. And to be honest, if the reporters did NOT include Boone County’s only Black state representative David Tyson Smith that’s a very serious oversight. In the Missourian, the one-line response is attributed to retired educator Sheila Plummer, the only black woman recognized among several who testified.

What does it look like to decenter the white men’s voices and presence in reporting on history when it comes to slavery and center instead of on the people whose identities are singularly subjugated in their depiction? Have reporters and J-students visited the mural? Is any art on display in city or county buildings by people of color? The children’s services building off Keene has a photo of a white man on the wall and that’s it. A sheriff/police officer sits in the room. There are no toys for children. The hospitals? Whose pictures and art are represented? The mural-like other representations in town -- including the Thomas Jefferson statute are representative of who “owns” i.e. controls public space.

Finally -- and this is more of a critique of people who claim to be liberal. As Charlene Carruthers notes from her book: "Unapologetic": Charlene Carruthers on Her Black, Queer and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movement: Liberalism gives room for/to bullshit. (Paraphrasing). It seemed to me that the Judges/Attorney spoke about how much their clients don’t like it and it impacted their “business” and a few said the mural perpetuated “mistrust” in the system.

There are many layers of ironies. It feels sorta third-person, but maybe their presentations made them feel like they’ve done something good— a way to repent for their apathy… but to me, their hearts were stuck somewhere in appearances. Where have the attorneys and judges been to dismantle cash bail or the brutal inequities of the system they maintain? Seriously. Justice is not blind or colorblind. Never had been. Structurally the mural does nothing to ameliorate the injustices of the system they work in and maintain. If anything the mural is staring back at them and shouting: “This picture hasn’t changed”.

Judge Crane walks in the same lane as Sheriff Carey. Decentering themselves and their whiteness is completely impossible.

I was pleased that my son Ian had the last word engaging a query from a former student of Sidney Larson who yelled out to the commissioners: “Have you thought about how much it would cost to move the mural--have you considered the dangers of moving it?” Ian piped up from the conference call microphone quickly: “Probably cheaper to paint over it!”

In closing, what does it mean for white people to accept that non-white people do not like or agree with the way they are depicted from the stance of a white male perspective? Why is it that whiteness can not concede that Black people’s perspectives are credible and valid? Why must our lived experiences be cross-examined by white society’s performative and ahistorical perspective that denies centuries of political indifference to equality and equity?

What the meeting last night demonstrated is that Boone Co has yet to reckon with its history of slavery — and how that history continues to ride shotgun in the present! Racism is a white people problem, and white people need to get busy fixing it.

In the meantime, visual artist Jessica Thornton gives me hope for an artistic perspective that provides a way forward.

Home